Source: Iberia

- On this precise day, 75 years ago, Iberia established its first transatlantic route to Buenos Aires, with stopovers at Villa Cisneros – then considered the best natural airport in the world, on the shores of the Saharan desert – Natal and Rio de Janeiro. The first flight, although without paying passengers, took off from Barajas airport on September 22, 1946.

When World War II ended, and as the political and economic circumstances of Spain allowed it, Iberia drew up the basic lines of action to allow the expansion of its network of services. Among its most immediate objectives was the establishment of the first transatlantic line, an endeavor that was a real challenge at the time due to the severe restrictions derived from the war and, above all, from the situation in which the country was.

To do this, in January 1945, with the world still at war, the company signed a contract with Douglas for the acquisition of three new DC-4 aircraft (Skymaster), at a price of US$400,000.00 each and deferred payment, which It would make it possible to face a substantial change in the expansion of the international network, then a clear objective, since this would allow generating income in foreign currency, essential for the acquisition of airplanes, engines and spare parts.

The keys to a new continent

It was thus, with the arrival of the new planes, that Iberia established its first transatlantic route to Buenos Aires, with stopovers in Villa Cisneros – then considered the best natural airport in the world, on the shores of the Saharan desert – Natal and Rio de Janeiro. The first flight, although without paying passengers, took off from Barajas airport on September 22, 1946.

The expedition was formed by the president of the company, Jesús Rubio Paz; the managing director, César Gómez Lucía; the general director of Civil Aviation, Juan Bono and a commission from the Ministry of Commerce. In total, 28 people, including Iberia sales and maintenance technicians.

A complex journey

After the stopover in Villa Cisneros, the trip continued throughout the night until landing at nine in the morning, local time, on the September 23rd, in Natal (Brazil). While there, bureaucratic problems arose, which delayed the continuity of the trip for 24 hours. At dawn the next day, the plane took off for Rio, an unscheduled stopover, forced by the authorities to clarify certain doubts regarding the following flights of what was to be a regular line. Upon reaching the Brazilian coast, it was reported that a blanket of clouds covered from the north of Rio to Sao Paulo, which forced to fly over the city until it was decided to cross it, when fuel was almost exhausted.

On the morning of the 25th the trip continued to Buenos Aires, landing in the afternoon at the Morón airport, to the praise of the crowd, after 36 hours flying and a little more than two days of travel. The expedition remained in Argentina until October 8, taking multiple steps to ensure the establishment of the line and signing commercial agreements. On the return trip to Spain, a group of Argentine authorities and guests came on board, making stops in Recife (Brazil) and Villa Cisneros, where they rested the night of the 9th, arriving in Barajas in the afternoon of October 10.

Route consolidation

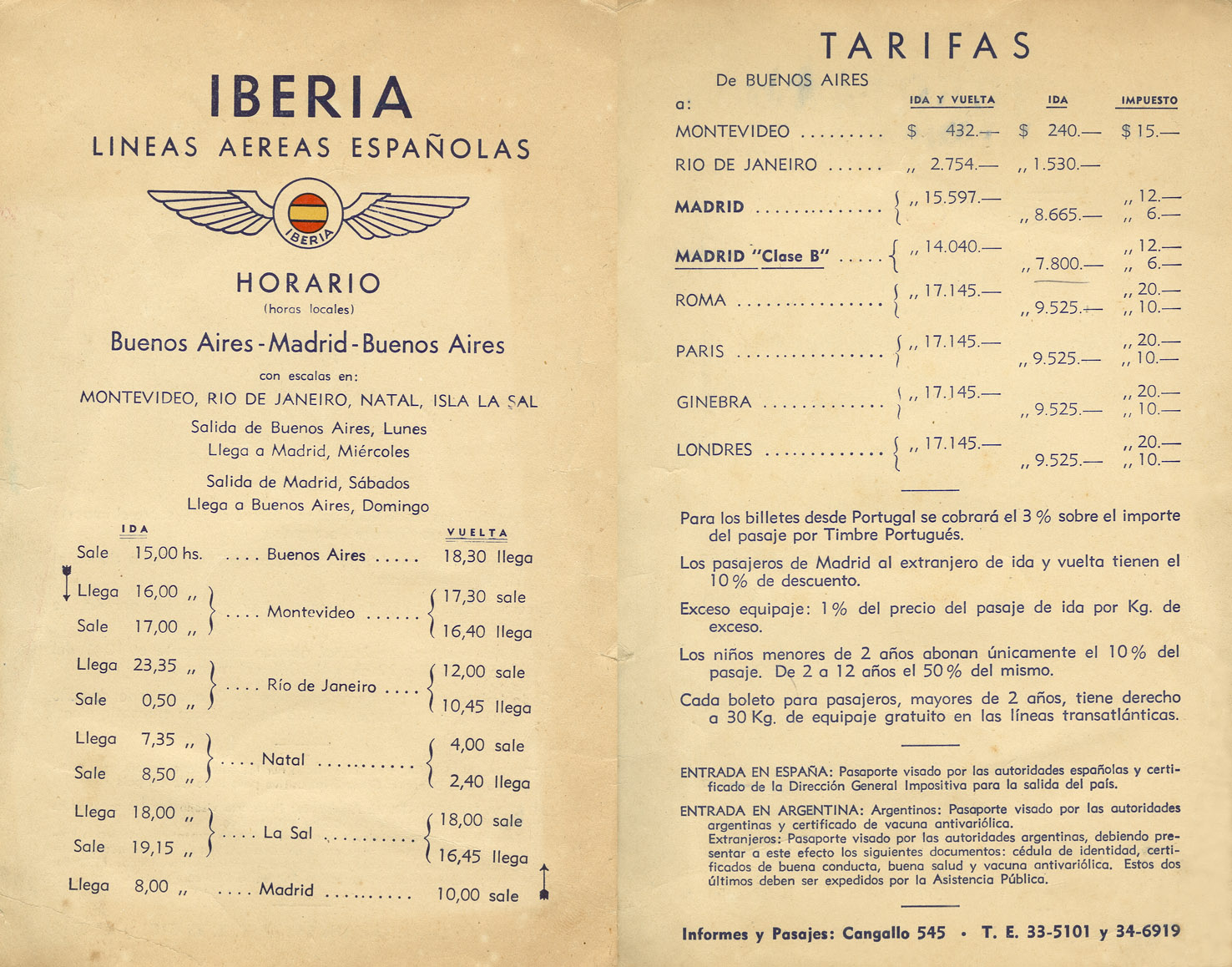

As of October 15, line 1215 was established on a regular basis every ten days, which changed to weekly in May 1948. The first commercial flight was in charge of the pilots José María Ansaldo and Fernando Rein Loring, two historical figures of the Spanish commercial aviation.

The plane took off from Barajas airport at noon on Saturday and made stops in Villa Cisneros and Natal, where it arrived at three in the morning, local time. In order to comply with the precept of hearing mass on Sunday, and to avoid that the Iberia itinerary could be criticized for this reason, it was decided to set up a shed that specially enabled this function, after the Pope had granted the mandatory authorization at the request of the bishops of Madrid-Alcalá and Natal. In this way, after traveling over the Atlantic during the night, the passengers who so desired could attend the religious service, which was almost always the majority, as well as the crew, who acted as altar boys and took communion.

The DC-4 trip then continued to Montevideo and Buenos Aires, where it arrived on Sunday afternoon. The return trip returned on Mondays following the same route. On Tuesday night resting was at the Villa Cisneros parador and the next morning the flight continued its route, landing in Madrid on the afternoon of the same day.

In the first trips, the plane, although it had capacity for 44 seats, only offered 24 seats for the passenger, since the rest were occupied by four berths and seats for the crew. The price of the ticket was set at 7,250 pesetas or 659 dollars at the exchange rate of the time.

“The palace of Aladdin”

Iberia chose the stop-over at Villa Cisneros, where it built a parador with 30 rooms and 50 beds, which was baptized “The Palace of Aladdin.” Electricity for lighting and other uses of the property was obtained through wind energy, taking advantage of the constant wind that blows in the desert. The parador operated for just six months, when it was found that the hours of stay were not well received by the passengers, so the stopover was replaced by the island of Sal (Cape Verde), since this airport was opened to traffic, which it allowed to shorten the duration of the jump over the Atlantic.

Passengers had to present themselves the day before traveling at the Iberia offices in Madrid with their passports, medical certificates and tickets, to fill out the forms and present them sufficiently in advance at the consulates of Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina for their corresponding visa. For those who came from other provinces, Iberia provided accommodation the night before at a guest house near the Palace Hotel, which was the meeting point for boarding the flight.

The full weight of the aircraft and the passenger was critical, and therefore at the time of boarding the passengers, as well as their checked and carry-on luggage, were weighed on a scale.

The commercial success of the line was spectacular; the demand was impressive both in Spain and in Uruguay and Argentina, especially as a consequence of the forced parenthesis between wars that made travel impossible. In 1946, the average load factor of the route was 90%.

The Super Constellation

In 1957 the Super Constellation, considered the most beautiful aircraft of all, replaced the DC-4 on transatlantic routes.

It had capacity for 74 passengers, 14 in first class and 60 in tourist. The first class was located at the back of the plane, where there was less noise and vibration. In addition, there was the possibility of unfolding two beds, isolated from the corridor by means of curtains and a section of two facing armchairs and with folding tables. Although it had four engines, it was considered the best triple-engine crossing the Atlantic, due to the frequency with which one of them had to be stopped mid-flight.

It was followed by the DC-8 in the 60s, the DC-10 in the 70s, later the legendary Jumbo Boeing B-747, the Airbus A-340 and today, the A-350.

The figure of the stewardess is born

To carry out this long journey of more than 36 hours in the four-engined Iberia, the airline thought of including a service attended by hostesses, new professionals who would attend to passengers during the flight.

Airviaries, flight attendants, butlers or provisionals were some of the names proposed for this profession. The person in charge of making such a difficult decision was César Gómez Lucía, director-general of Iberia at that time, who chose the name of hostesses.

At the first call for employment for hostesses, several young women appeared, including 11 “horchateras” from Madrid. One of the most important requirements was knowledge of English.

Once the selection process was finished, four were the people chosen for this new job; Pilar Mascías, Marichín Ruiz, María José Ugarte and Ana Marsans.

Before starting the flight, they were in charge of distributing to the passengers a safety pamphlet with recommendations such as “avoid smoking cigars so as not to disturb your neighbors”, or warnings such as “do not be alarmed if during the night you see flames coming out from the engines as this indicates direct escape of gases”.

During the trip, their job consisted of transmitting security and confidence to his passengers, as well as offering information about the flight and serving the food in small cardboard boxes containing fried chicken, Spanish omelette, hard-boiled eggs or chocolates. This meal service on board was completed with different drinks, among which was coffee and water served in earthenware cups.

At that time, bread was scarce in Madrid so an Iberia employee was in charge of going to nearby towns to buy this food. In addition, some passengers did not allow young women to be their waitresses, so these gentlemen opened their own bottles, thus showing off their chivalry.

Although they did not wear a uniform on their first flights, they later had two sets of them. A white suit made with parachute fabric for the summer and a navy blue suit for the rest of the year. Both consisted of a Saharan jacket with four pockets, a long skirt and a hat for the rest of the year.

Over time these uniforms were altered by removing the hat they wore or changing the color of the summer uniform since it easily got dirty. Years later, their uniforms changed completely thanks to the work of important dressmakers such as Elio Berhanyer, Pedro Rodriguez, Pertegaz or Adolfo Domínguez.

In 1947, a year after the first flight of these hostesses, the first male flight attendant of Iberia joined. Fernando Castillo was the name of this young man who before starting in Iberia worked as a waiter in a luxury restaurant in Madrid.